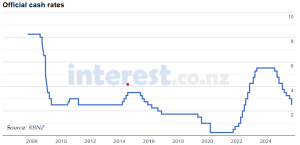

The Official Cash Rate (OCR), which influences the floating mortgage rate, and short term fixed-rates, dropped last week. Everyone has a view around what SHOULD happen, but no one’s talking about what WILL happen. Most economists predict the Reserve Bank will deliver perhaps one more 0.25% cut, with Kiwibank being the outlier forecasting a 2.0% terminal rate.

While these predictions are very sound, and based on mainstream economics, I think we’re living in a new regime, where interest rates have to go lower than the previous cycle, in order to maintain stability in the financial system. Interest rates remain one of the primary drivers not only of the economy, but of wealth creation and preservation. As a property owner, it doesn’t seem right that a central bank has this much influence over our retirement strategy, but they do.

I believe we’ll see an OCR of between 1.0% and 1.5% this time next year, and here’s why:

Central Banks Were Already Struggling With Inflation Before The Pandemic

Before anyone had heard of a global pandemic, central banks were already fighting a battle with inflation, just not the way you’d expect. Perhaps subconsciously, I genuinely used to believe inflation came from ‘too much economic activity’, and the role of a central bank was to occasionally hike rates as a way to handicap things, until a new state of ‘equilibrium’ was achieved. When considering the pattern observed post-GFC, it was clear the OCR was repeatedly reduced, in order to create inflation? Yes, create inflation. The natural state of any economy infused with technology, is that things become cheaper over time. Lower interest rates, which results in more credit creation, is how this is syphoned off. Increased borrowing with no increase in productivity will often masquerade as GDP (gross domestic product), but in reality, most of our economic growth is a mirage

New Zealand’s OCR sat at just 1.0% in early 2020, before any pandemic emergency measures were implemented. The RBNZ had been gradually lowering rates since the GFC in a largely unsuccessful attempt to reach their inflation mandate of 1-3%.

The RBNZ struggled repeatedly, to get inflation to appear, which would justify maintaining higher rates after 2008. They eventually found justification to cut rates again after the Christchurch earthquakes in 2011. As an Aucklander, why did my mortgage costs need to drop to support the rebuild? I didn’t need to benefit when those affected were going through so much.

In reality, it might not have even been about ‘supporting the economy’, it may have been an excuse to inject more currency into an unproductive economy until inflation reached the magical 1-3% range.

If central banks couldn’t sustainably maintain higher rates prior to March of 2020, what makes us think they can hold current settings when economic weakness persists?

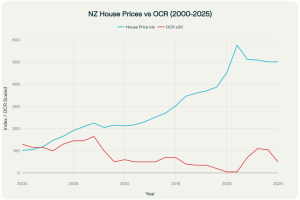

Could it be, that rising house prices over time is the actual goal, despite what the politicians say?

A Lower OCR Is A Systemic Inevitability

As mortgage costs approach rental equivalence, purchasing activity increases, pushing prices higher and forcing subsequent buyers to borrow even more. This is credit expansion, and it’s how new money enters the private economy.

New Zealand’s economy functions, for better or for worse, as a property market powered by credit creation. Property is a conduit by which new currency enters our economy. The function of banking is so entrenched in New Zealand’s economy that it cannot be undone without systemic collapse. It’s a parasite/host relationship, and it can’t be abandoned.

But a lower OCR will place pressure on our limited housing supply? Yes

And lower rates will lock an entire generation out of property. Yes

But won’t lower interest rates will re-ignite further inflation and necessitate higher interest rates for longer? Maybe

It’s not pretty, and I wouldn’t vote for it, but a much lower OCR ‘is the way’.

The primary driver of property values is borrowing costs, so for house prices to rise consistently, interest rates must generally decline.

The median income simply cannot keep pace with median house prices under normal circumstances, which means the only sustainable mechanism to maintain housing market activity is progressively lower interest rates with each cycle.

People often express frustration with this system, looking to politicians of the left and right, expecting action. There appears to be no viable alternative without triggering economic devastation. The RBNZ may not explicitly state their objective as house price inflation, but credit creation through residential property lending has become the primary monetary transmission mechanism. Like any Ponzi scheme, there’s no stopping this train. One-year mortgage rates have already begun tracking toward sub-4% levels, and if the OCR continues its descent, rates in the 3% range (or lower) become mathematically inevitable. It’s not fair, and it’s not what some may want, but it’s the reality we’re faced with.

Victims or Participant?

The reality is, because interest rates MUST continue their march downwards, property prices will inevitably increase. The temptation is to argue about what should happen, but meanwhile, the options there to act based on what will happen.

For property owners, mortgage expenses represent the single largest monthly outflow, and as this cost declines, the critical question becomes ‘what to do with the savings’? Younger investors may find greater long-term benefit in deploying excess cash into investments rather than aggressive debt repayment. On the other hand, lower interest costs can be converted into more aggressive repayments off principal. All you need to is is keep repayments constant when rate cuts flow through.

For those looking to enter or upgrade within the property market, prices currently feel elevated but will likely continue appreciating as rates fall further. Remember, investors typically re-enter markets after prices have already risen and the gap between rental income and ownership costs has narrowed.

Prediction: The OCR will hit 1.0-1.5% by this time next year, driving one-year mortgage rates to approximately 3%

The structural economic model of credit creation through housing can’t function with an OCR at 2.5% or higher. Yes, this can’t go on forever, but we have at least one more cycle to run. It’s not about what’s ‘just’ or even ‘sustainable’, it’s whether you want to participate, or spectate. Given the economic forces at play and the institutional constraints facing central banks, can anyone truly afford to ignore the inevitable direction of monetary policy?

*Disclaimer: This article is opinion only. Do not rely on any claims or perspectives without relying on your own advice, and/or complete your own due diligence before making decisions.